Written by Rodney D. Sieh, rodney.sieh@frontpageafricaonline.com

Published: 08 March 2016

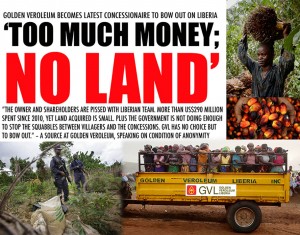

“The owner and shareholders are pissed with Liberian team. More than US$290 million spent since 2010, yet land acquired is small. Plus the government is not doing enough to stop the squabbles between villagers and the concessions. GVL has no choice but to bow out” – A source at Golden Veroleum, speaking on condition of anonymity

Monrovia – A recurring Liberian nightmare is forcing another concessionaire out the door. FrontPageAfrica has reliably learned that the palm giant, Golden Veroleum, the world’s second largest palm producer has grown weary of lingering disputes with villagers and is unhappy with very little prospects after spending a whopping US$290 million since 2010.

Multiple sources have confirmed to FrontPageAfrica that GVL, a subsidiary of Golden Agro Resources based in Indonesia with investment of 1.6 billion, is about to be sold out to another Indonesian company, partnering with a European company. Already, at least 400 Liberians have been laid off with full benefits paid and employees are said to be bracing for an uncertain future. Sources tell FrontPageAfrica that most of the expatriates’ work permits have expired and Labor Ministry could soon come knocking.

GVL owners are also expressing concerns that the global economic meltdown is a major factor in the decision to sell off its assets. The company owners, according to sources have been upset with the Liberian team after spending a whopping US$290 million since 2010 but failing to acquire sufficient land to plant nurseries.

GVL came under fire last year when a Global Witness report slammed the company for bringing together scores of people in Liberia during the Ebola outbreak to sign over thousands of acres of land as part of a planned expansion, and also allegedly intimidated landowners and opponents of its operations. According to the GW report, GVL signed four memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with local communities between August and November 2014. The MoUs cover more than 13,350 hectares (33,000) acres of collectively held lands.

“Each of these MoUs is signed by hundreds of people, suggesting that the company was bringing together large numbers of community members at a time when people were panic-stricken and avoiding any physical contact or public gatherings,” said the report, The New Snake Oil. One MoU was signed by 519 people in the same week last October that the 2,400th death from Ebola occurred in Liberia, Global Witness said. At that time, NGOs had little access to south-eastern Liberia.

Under a 2010 concession agreement, Liberia’s government agreed to lease GVL about 220,000 hectares (543,400 acres) of land over a period of 65 years to develop its palm oil operations in five south-eastern counties: Sinoe, Grand Kru, Maryland, River Cess and River Gee. Land clearance began in December 2010, halted two years later by a freeze on plantation expansion requested by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil in response to community complaints. Expansion began again in 2013 in Sinoe and Grand Kru, and several thousand hectares of land are believed to have been cleared and planted across these counties. Food insecurity is particularly prevalent in south-eastern Liberia.

GVL has been at war with villagers claiming infringements from the powerful oil palm firm. Last June, protesters in Butaw, Sinoe County stormed and vandalized the premises of GVL, as the company began renewing its commitment to local communities in Sinoe and Grand Kru counties. The riots started after Butaw Youth Association staged violent protests demanding an immediate meeting with a top visiting GVL official.

Entrances were blocked by the Butaw Youth, preventing vehicle and employee movement, while stones were thrown at managers and facilities. Several company’s vehicles were damaged, while others sustained body injuries and properties looted, thus causing dozens of GVL employees to flee into the bush for safety. The Butaw Youths have been engaged in boundary dispute between Butaw and the neighbouring community of Murrysville. GVL had previously indicated that its corporate policy and international standards dictate that the companies not expand into areas with boundary disputes.

A recent report by a rural women agriculture group under the banner ‘Natural Resource Women Platform’ catalogued abuses and untold suffering that they have allegedly been subjected to by concession companies operating in Liberia. The group was founded in 2010 by uneducated marginalized, rural poor and urban slum dweller women who are involved with rock crushing, charcoal and palm oil production, farming, sand mining and fishing.

A major factor contributing to GVL’s looming exit, sources say is Liberia’s inability to deal with recurring land squabbles in difficult concession areas dimming prospect for growth due to communities’ refusal to offer land. Stephen Binda, the company’s communication spokesman, when contacted said he could not comment. But residents have been unhappy alleging that companies operating in the mining, agricultural and extractive sectors failed to seek their free, prior and informed consent before commencing works in their areas.

Last year, residents complained that New Liberty Gold Mine Project, a company mining gold in the county uprooted an entire community against the wish of residents, especially women who cultural shrines were destroyed. Last May, in response to the residents, the company, in a damning letter, agreed in principle to some of the complainants’ recommendations but expressed disappointment that the complainants have continued to misrepresent the situation.

The complainants alleged that GVL had developed plantations on disputed land by referring to the Provisional Memorandum of Understanding Incorporating Social Agreement between Numopoh Community and Golden Veroleum (Liberia) dated 28th April 2014. They quote that “Phase I of GVL development, consisting of 629 hectares, where already sits the nursery 86 hectares and facilitates of 60 hectares and 483 hectares of planting area is recognized by the Numopoh and GVL being included in an ongoing land claim by the Doe Wollee Nyannye communities.”

Liberia’s investment climate has taken a hit in recent months boggled down by global financial meltdown. Steel giant, ArcelorMittal’s financial debacle which has disrupted mining activities putting hundreds out of work and delay the key Ganta-Yekepa Road project spiraling a damper on billions of dollars’ worth of investment trumpeted by Liberia’s first post-war democratically-elected government when it took office in 2006. The investments were seen as key to helping the country restore its economic sanity after more than a decade of war and chaos. But many companies have seen profits margin decline and feeling the pinch of the global financial meltdown trend.

Several multinational companies which came to Liberia with billions of investment have since left Liberia in the cold. Among them are BHP Billiton, Putu Mining, Buchanan Renewables and a host of others. BHP, which signed an estimated US$3 billion agreement with Liberia, but sold its interest to Cavala in 2015. Prior to the BHP Billiton agreement, Liberia had concluded two other major deals in the sector, with ArcelorMittal at $1.5 billion and China Union at $2.6 billion.

The news of GVL’s planned sale comes as the Liberian government is considering moving the Butaw violence case from Sinoe to Rivercess County due to security concerns. Rights activists have questioned the continued imprisonment of those arrested during the melee after two terms of court, prompting some to believe that their arrest could become an election issue in the county come 2017. There have been some speculations that those arrested could be granted clemency as part of a campaign move to pull votes in 2017.

GVL, according to sources have shockingly not contributed to Sinoe and Grand Kru County development fund as other companies do but have provided scholarships to agriculture students. Vice President Joe Boakai during a meeting with some Indonesian officials in 2014 took GVL to task over the quality of workers’ housing and challenged GVL to improve its social programs and community services.

It is unclear what the company’s imminent takeover plan would mean for ongoing simmering tensions between villagers and concessionaires. Even if a new company comes in, many fear they could endure similar problems, a nagging issue that has dogged the Sirleaf administration and kept villagers at war with a concession company now frustrated that there simply isn’t enough land to grow nurseries and get returns on its investment.