18th February 2014

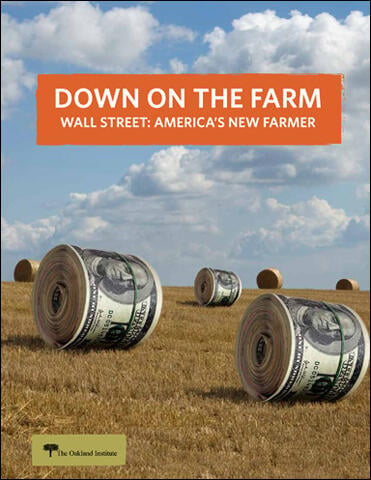

The first years of the twenty-first century will be remembered for a global land rush of nearly unprecedented scale. An estimated 500 million acres, an area eight times the size of Britain, was reported bought or leased across the developing world between 2000 and 2011, often at the expense of local food security and land rights. When the price of food spiked in 2008, pushing the number of hungry people in the world to over one billion, the interest of investors spiked as well, and within a year foreign land deals in the developing world rose by a staggering 200 percent. Today, enthusiasm for agriculture borders on speculative mania. Driven by everything from rising food prices to growing demand for biofuel, the financial sector is taking an interest in farmland as never before. As the Oakland Institute reported in 2012, a new generation of institutional investors—including hedge funds, private equity, pension funds, and university endowments—is eager to capitalize on global farmland as a new and highly desirable asset class.

But the thing most consistently missed about this global land rush is that it is precisely that—global. Although media coverage tends to focus on land grabs in low-income countries, the opposite side of the same coin is a new rush for US farmland manifesting itself in rising interest from investors and surging land prices, as giants like the pension fund TIAA-CREF commit billions to buy agricultural land. One industry leader estimates that $10 billion in institutional capital is looking for access to US farmland, but that number could easily rise as investors seek to ride out uncertain financial times by placing their money in the perceived safety of agriculture.