GRAIN | 16 October 2012 | Presentations, Other publications

Every day there are new stories of companies buying up farmlands. Malaysian palm oil giants buying up lands for plantations in West Africa. Wall Street bankers taking over cattle ranches in Brazil. Saudi businessmen signing land deals in the Philippines. The latest dataset on land grabs claims that 10 million hectares of land have been grabbed by foreign companies on average every year since 2007.

The result is that a small number of people are taking over more and more of the world’s farmlands, and the water that goes with it, leaving everyone else with less, or none at all. As the world plunges deeper into a food crisis, these new farmland lords will hold sway over who gets to eat and who doesn’t and who profits and who perishes within the food system.

The global farmland grab is only happening because people are pursuing it. The number of land grabbers is small, in contrast with the high number of people displaced by their actions. They are mostly men, often with experience working with agribusiness companies or banks. Some of them sit at high-levels of government and intergovernmental agencies, and sometimes at the highest levels. They operate out of the big financial centres of the world and often get together at farmland investor meetings, whether in Singapore, Zanzibar or New York City.

We think it might help the debate over land grabs to pull back the curtain a little on who these people are. So we’ve pieced together a slide show that tells about some of those who have been actively pursuing or supporting farmland grabs. It’s an emblematic set of land grabbers, not a comprehensive one. Knowing who’s invovled can also help us in pressuring the land grabbers to stop. Each landgrabber profile indicates who his or her friends are and provides resources for those who want further information or to pursue actions.

Download the slideshow in PDF (5.6 MB) or a text version in PDF (713 KB).

(For a previous profile of people grabbing land in Africa, see Meet the millionaires and billionaires suddenly buying tons of land in Africa, by Courtney Comstock, published by Business Insider, based on research by the Oakland Institute.)

Profiles of some of the people pursuing or supporting large farmland grabs around the world

Jean-Claude Gandur (Switzerland)

Jose Minaya (US)

Sai Ramakrishna Karuturi (India)

Calvin Burgess (US)

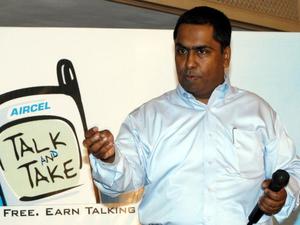

C “Siva” Sivasankaran (India)

Neil Crowder (UK)

Michael Barton (UK)

Meles Zenawi (Ethiopia)

Eduardo Elsztain (Argentina)

Susan Payne (Canada)

Dr. Hatim Mukhtar (Saudi Arabia)

Theo De Jager (South Africa)

The World Bank Group

Antonio L. Tiu (Philippines)

Hou Weigui (China)

“I don’t feel guilty of doing anything immoral”

“I don’t feel guilty of doing anything immoral”

(Switzerland)

Owner of Addax Bioenergy

In April 2012, farmers in Sierra Leone gathered for an assembly of communities affected by large-scale foreign land investments. Many participants came to speak about a 10,000-ha sugar-cane project operated by Addax Bioenergy, an ethanol company owned by Swiss billionaire Jean-Claude Gandur. “We’ve been evicted from our farmland without compensation,” said Zainab Sesay, a woman farmer from the project area. “Now I don’t have a farm. Starvation is killing people. We have to buy rice to survive because we don’t grow our own now,” said Zainab Kamara, another farmer displaced by the Addax project.

In his Geneva headquarters, surrounded by his impressive collection of art and antiquities, Gandur tells a different story. He explains to reporters that his project complies with the social and environmental standards set by the African Development Bank, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and the European Union. Indeed, over half of the company’s project costs are met by development banks. “That’s why I don’t feel guilty of doing anything immoral,” says Gandur.

Gandur built his fortune, estimated at US$2 billion, trading commodities and buying up oil concessions in Nigeria and other African countries. In 2009, he sold his interests in the oil business and turned his attention to the continent’s farmlands. Fuel is still his focus, but now it’s ethanol, not petroleum.

For his first big project, Gandur selected Sierra Leone, a war-ravaged country where malnutrition affects one third of the population. It’s a controversial spot to grow sugar cane for the production of ethanol for export. Not only has the company’s takeover of 10,000 ha of “fertile and well-watered” land and forest displaced local food production, it’s also taking away access to water for farmers living downstream. The company’s sugar-cane plantation will use 26% of Sierra Leone’s largest river flow during the driest months, February to April.

Gandur says that his ethanol project, due to become fully operational in 2013, is “a good way to bring back agriculture in Africa.” But good for whom? The Swiss group Brot für Alle carried out a basic analysis of the company’s numbers and found that Addax would take home an annual return of US$53 million, about 98% of the value added by the project. The company’s 2,000 or so low-paid workers would get only 2% of the value, while the landowners who leased their land to the company would receive a mere 0.2% of the value added. All told, says Brot für Alle, the project will provide less than US$1 per month to each person affected by the project.

Friends of Gandur:

Swedish Development Fund (Swedfund): In December 2011, Addax Bionergy announced that Swedfund had become a major shareholder of its mother company, the Addax & Oryx Group.

Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO): Along with the African Development Bank and several other development banks, FMO provides debt financing to Addax Bioenergy and is a major shareholder in its mother company, the Addax & Oryx Group.

Going Further:

- Action for Large-scale Land Acquisition Transparency (ALLAT), a network of civil society organisations and landowner and user associations in Sierra Leone, created to monitor land investments throughout the country and to sensitize communities (allat@greenscenery.org)

- Brot für Alle’s report “Land grabbing: the dark side of ‘sustainable’ investments“

*

!["It's too risky for a company like TIAA–CREF to go into these areas [such as Africa] because we're sure going to be in the headlines a year from the time we make the investment."](http://www.grain.org/media/BAhbB1sHOgZmSSI4MjAxMi8xMC8xNi8wOV80OV8wMl81MjRfNDE3NzdfMTAzODM4OTE1N18yODQzX24uanBnBjoGRVRbCDoGcDoKdGh1bWJJIgkzMDB4BjsGVA) “It’s too risky for a company like TIAA–CREF to go into these areas [such as Africa] because we’re sure going to be in the headlines a year from the time we make the investment.”

“It’s too risky for a company like TIAA–CREF to go into these areas [such as Africa] because we’re sure going to be in the headlines a year from the time we make the investment.”

Managing Director of the Teachers Insurance & Annuity Association – College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF)

Slave labour, theft of indigenous lands, destruction of forests and savannas – these are some of the hallmarks of Brazil’s sugar-cane industry. Now, thanks in part to an influx of foreign cash, the industry is booming as never before. Over the past ten years, the area devoted to sugar cane in Brazil has nearly doubled, from 4.8 to 8.1 million ha, with at least 1,000 ha of land converted to sugar-cane plantations every day. Most of this expansion is happening in the country’s , a biodiverse savanna that is home to around 160,000 plant and animal species, many of them endangered. Brazilian workers are paying the price too: the industry is one of the most dangerous, exploitative and poorly paid sectors in which to work. And, as sugar cane expands, land is taken out of food production into the hands of Brazil’s sugar barons, in a country where 3% of the population already holds almost two-thirds of the country’s arable land.

Teachers and professors in the US may not know it, but their retirement savings are being used to profit from this expansion of sugar-cane plantations in Brazil. Under the helm of its Managing Director, Jose Minaya, New York-based TIAA–CREF, the biggest fund manager of retirement schemes for US teachers and professors, has channelled hundreds of millions of dollars into a fund that acquires Brazilian farmland and converts it into sugar-cane plantations.

The fund is called Radar Propriedades Agrícolas. It was launched by Brazil’s largest sugar-cane producer, Cosan, to identify properties in Brazil that it could acquire cheaply, convert mainly into sugar-cane plantations, and then sell at a profit within a few years. Cosan, which owns 19% of the fund, manages the fund’s investments and retains first rights to acquire lands before Radar puts them on the market. The other 81% of the fund is owned by TIAA–CREF through its Brazilian holding company, Mansilla. At the end of 2010, Radar had spent US$440 million to acquire more than 180 farms in Brazil, covering 84,000 ha, with plans to spend another US$800 million in the near future to acquire 60 more farms, covering 340,000 ha.

TIAA–CREF’s farmland portfolio extends well beyond Brazil. Since 2007, the company has spent US$2.5 billion taking over farms around the world, turning hundreds of thousands of hectares in Australia, Poland, Romania and the US into corporate farms through its subsidiary the Westchester Group.

TIAA–CREF’s motto, however, is “Financial Services for the Greater Good” and, in 2011, it joined seven European institutional investors to launch the Farmland Principles, a set of five principles committing signatories not to engage in farmland deals that harm the environment or violate labour or human rights, or land and resource rights. Experience suggests that TIAA–CREF can be pressured to divest from the global farmland grab. It has already pulled out of investments in companies operating in Darfur, and is now the target of a nationwide campaign to get it to divest from companies that profit from the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands.

Friends of Minaya:

AP2: The Swedish National Pension Fund’s second vehicle, AP2, sunk €177 million (US$240.7 million) into TIAA–CREF’s Westchester Group in 2011 for the acquistion of farmland.

Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec: In May 2012, Canada’s second-largest pension fund manager announced a C$250-million investment in a global farmland fund managed by TIAA–CREF, in which AP2 and the British Columbia Investment Management Corporation (bcIMC) also participating.

Royal Dutch Shell: In 2010 it set up a US$12-billion, 50:50 ethanol joint venture with Cosan that Radar says will increase its opportunities for farmland investments.

Going further:

- Brazil’s Comissão Pastoral da Terra

- Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement/Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST)

- US Food Sovereignty Alliance

- US campaign to stop TIAA–CREF from investing in companies that profit from the Israeli occupation

- Carlos Vinicius Xavier, Fábio T. Pitta and Maria Luisa Mendonça, “A monopoly in Ethanol production in Brazil: The Cosan–Shell merger“, Milieudefensi and TNI, 2011.

*

Sai Ramakrishna Karuturi (India)

“What Karuturi is doing is what Africa needs, wants and deserves.”

“What Karuturi is doing is what Africa needs, wants and deserves.”

CEO and Founder of Karuturi Global Ltd

When people talk of land grabs in Africa, a name that crops up often is “Karuturi”. Sai Ramakrishna Karuturi, India’s “King of Roses”, made his fortune farming roses in East Africa for European markets. Now he’s ploughing those profits into his next big African project: food production.

Karuturi has huge ambitions. He wants to set up farming operations on more than 1 million ha, mainly in eastern and southern Africa, to produce maize, rice, sugar cane and palm oil. “In 5–10 years time I would like to be seen and compared with peers such as Cargill or ADM or the Bunges of the world,” he says. He’s already taken control of 311,700 ha in Ethiopia, and is negotiating for another 370,000 ha in Tanzania. Plans are also in train for a farm project in the Republic of Congo, and fruit and vegetable farms in Sudan, Mozambique and Ghana.

Karuturi calls Africa’s farmlands “green gold”. It’s easy to see why. For every hectare he puts under rice production on his farm in Gambela, Ethiopia, he expects US$660 in profit per year. His company will have to pay only US$46 per hectare per year for the land, labour and water it uses.

But Karuturi’s skill as a farmer is questionable. His first maize harvest in Gambela was destroyed by a flood that overwhelmed his canal system, causing US$15 million-worth of damage and requiring a further US$15 million for reinforcement. Unable to bring all the lands he’s leased into production on time, he has tried to sub-let chunks to Indian farmers on a revenue-sharing basis. This has caused problems with the Ethiopian government. When several hundred Indians arrived at Addis Ababa airport at the end of 2011, ostensibly as machine operators for the Karuturi farm, the Ethiopian Government turned them away.

Karuturi’s operations are also deeply entangled in land conflicts, especially in Gambela. According to a 2012 report by Human Rights Watch, the Ethiopian Government is forcibly relocating 70,000 indigenous people in western Gambela to new villages that lack adequate food, farmland, healthcare, or educational facilities, in order to make way for large-scale agricultural projects of foreign investors, including Karuturi. The report said that crops belonging to local Anuak communities were cleared without consent to make way for the Karuturi operations, and that residents of Ilea, a village of over 1,000 people within Karuturi’s lease area, were told by the Ethiopian government that they would be moved in 2012 as part of its “villagisation programme”. Karuturi, however, denies any connection between his company’s activities and the government’s villagisation programme. He says the report is “hogwash” and “a completely jaundiced western vision”. He even denies that the villagisation programme exists.

Friends of Karuturi:

Djibouti: Signed a contract for Karuturi to supply it with 40,000 tonnes of food per year at international market prices.

Government of India: Funds Karuturi through the Exim Bank and Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services Limited.

John Deer Co.: Supplies Karuturi with tractors for its operations.

World Bank: Karuturi is in final negotiations with its Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency for political risk insurance.

Going further:

- Anywaa Survival Organisation, a UK-based group supporting the Anywaa people of Gambela, Ethiopia

- Human Rights Watch report, “Waiting here for Death: Forced Displacement and ‘Villagization’ in Ethiopia’s Gambella Region”

- La Via Campesina South Asia

*

“I disagree when people say, ‘Oh, you have to preserve the local culture.’ If you preserve it, people will starve, and you won’t have a culture to preserve.”

“I disagree when people say, ‘Oh, you have to preserve the local culture.’ If you preserve it, people will starve, and you won’t have a culture to preserve.”

CEO, Dominion Farms

Calvin Burgess moved to the US from Canada in 1976 and immediately got into the construction business. He soon built up a small empire, involved in everything from real estate to prisons, Mexican sock factories to pig farms. But in his late 50s Burgess felt it was time to do something “significant” instead of just “living a good life and dying a rich guy”. So, inspired by the stories of a woman at his church who had spent time in Kenya, he decided that he would go there too and see how he could make a difference. “God has plans for people’s lives,” says Burgess, “and I thought that maybe this was part of His plan for me.”

Burgess set up shop in western Kenya, in a place called the Yala Swamp. His idea: to build Africa’s largest rice farm – Dominion Farms – on 7,000 ha of land he acquired under a 25-year renewable lease agreement. But there was one problem. Thousands of people live, farm and raise livestock on the same land and depend on the same water source. Dominion Farms occupies 40% of the Yala Swamp, but the dam that the company built to irrigate its rice fields has flooded a much larger area and made it practically impossible for the local communities to raise livestock. Local residents also say that Burgess’s project destroyed their access to potable water, and that the regular aerial spraying of fertilisers and agrochemicals makes them and their animals sick.

For all this, they have seen little in return – a few hundred poorly paid jobs, and compensation packages of about US$60 per home for those who left. No wonder the locals are upset and demanding that Burgess and his company pack up and leave. In August 2011, Burgess filed a report with the police claiming that protestors had made threats on his life. “When you try to help these people all they do is complain,” says Burgess.

Undaunted by the opposition in Kenya, Burgess is now expanding into Nigeria, where he has acquired 30,000 ha in Taraba State, with the backing of former President Olusegun Obasanjo. In 2009, Burgess also announced that he had found investors to replicate his Kenyan farm model in Liberia on 17,000 ha.

Friends of Burgess:

Olusegun Obasanjo: The former President of Nigeria calls Burgess “a friend of Nigeria”, and has been intimately involved in helping Burgess to secure land in the country.

Going further:

- Kick Dominion Farms out of Yala campaign: facebook ; online petition

- Good Fortune (film)

- United Small and Medium Farmers Associations of Nigeria

*

“God stopped manufacturing land. The available land is at a premium.” – V Srinivasan, Sivasankaran’s close aide and CEO of Siva Ventures.

“God stopped manufacturing land. The available land is at a premium.” – V Srinivasan, Sivasankaran’s close aide and CEO of Siva Ventures.

CEO, Siva Group

C. Sivasankaran is one of India’s richest men, with a net worth of more than US$4 billion. He made most of his fortune pioneering sales of discounted PCs, mobile phone networks and broadband internet services in India. Sivasankaran keeps a low public profile and rarely gives public interviews. He is said to hold a “big bang approach to life” and is known to travel the world using his large fleet of private planes and yachts, staying in the most expensive presidential suites.

Lately, Sivasankaran has developed an interest in farmland. He started by taking major stakes in several Indian companies that have been acquiring farmland overseas: a 12% stake in Ruchi Soya, which has 50,000 ha on long-term lease in Ethiopia; a 10% stake in KS Oils, which has 56,000 ha for palm oil in Indonesia; and a 3% stake in Karuturi Global, which has a 300,000-ha land lease in Ethiopia.

Palm oil appears to be Sivasankaran’s favourite commodity. In 2010, he bought a minority stake in Feronia, a Canada-based company that acquired 100,000 ha for palm-oil and soybean production in the DR Congo, and then set up a joint venture with London’s Equatorial Palm Oil, taking 50% control of the company’s 170,000 ha in Liberia. Sivasankaran is now moving more directly into the field. He set up Biopalm Energy, a subsidiary of his Singapore-based Siva Group, and quickly snatched up 200,000 ha in Cameroon and 80,000 ha in Sierra Leone to produce palm oil for export to India, where it will be refined and sold.

“I’m a community land user, I live from farming,” says one woman from the Pujehun district of Sierra Leone, where Siva has taken land. “But now the investors, this Biopalm company [SIVA Group], has come and the Paramount Chief gives all the land away, even the land I use for farming, for collecting firewood, for native herbs [medicines], for everything. Now it’s all gone. I have nothing.”

All told, Siva has his hands on 756,000 ha of farmland, 670,000 ha of it in Africa.

Friends of Siva:

Singapore - provides a tax and financial haven for the registration of the Siva Group.

Going further:

- Action for Large-Scale Land Acquisition Transparency (ALLAT), a network of civil society organisations and landowner and user associations in Sierrra Leone created to monitor land investments throughout the country and to sensitise communities (allat@greenscenery.org).

- La Via Campesina South Asia

*

“Our goal is to feed Africa”

“Our goal is to feed Africa”

CEO, Chayton Capital

Neil Crowder, who describes himself as “a well-educated US citizen who four years ago would not have been able to locate Zambia on a map”, left Goldman Sachs to co-found Chayton Capital, a private equity fund which is spending US$300 million in agribusiness ventures in six African countries. The test case is Zambia, where it acquired a 14-year lease on 20,000 ha in Mkushi. It intends to aggregate its lands into a single operation, called “Chobe Agrivision”, within a 50-kilometre radius.

Crowder says that his company’s legacy will be to “teach Africans the latest farming techniques”, before they exit with an “18% cash on cash” return on investment.

“I don’t want to defend land grabs and we’re certainly not doing that,” says Crowder. “My view is that Africa needs to modernise its agriculture.”

But local farmers say that they have yet to see any benefit from Chayton Capital’s farm or the other commercial farms in the area. “So far they don’t help,” says Brighton Marcokatebe, a farmer from the nearby village of Asa.

If discontent among local farmers should one day boil up into demands for the land under Chayton’s control, Crowder has got his bases covered. “The World Bank has underwritten our assets for political risk,” explains Crowder. “We pay a premium for insurance and they guarantee against expropriation. Our political risk insurance protects us against civil disturbance.”

Friends of Crowder:

World Bank: Its Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency provides Chayton Capital with US$50 million in political risk insurance for its farm holdings in in Zambia and Botswana.

PSG Group: The South African financial corporation’s subsidiary, Zeder Investments, purchased a 96% stake in Chayton Africa in March 2012.

Mauritius: Provides Chayton with a tax and financial haven for its Chayton Atlas Agricultural Company.

Going further:

*

“Farm Lands of Africa’s programme represents a major breakthrough for the democratically-elected government of the Republic of Guinea in their priority plans for food self-sufficiency.”

“Farm Lands of Africa’s programme represents a major breakthrough for the democratically-elected government of the Republic of Guinea in their priority plans for food self-sufficiency.”

Founder and Chief Financial Officer of Farm Lands of Africa

Michael Barton got a taste for the profits that can be made in farmland during his five years as Chairman of New Hibernia Investments Ltd, a company launched by UK real-estate player Mark Keegan to buy farms in Argentina. When Keegan’s company sold its farms at a hefty profit in 2008, he and Barton turned their attention to Africa.

They enlisted the help of a former high-ranking officer in the British army, General Sir Redmond Watt, and Cherif Haidara, a Malian lobbyist intimate with West Africa’s inner circles of power. Their focus turned to Guinea, a country controlled by a corrupt dictatorship with millions of hectares of agricultural land. Haidara, who was put in charge of Guinea’s mining funds in October 2009, had already helped the UK company Sovereign Mines of Guinea, to which Keegan is connected, to get hold of five gold concessions covering a total of 3,600 sq km in the country’s gold-rich metallogenic belts.

Guinea was in a political mess at the time. Lansana Conté, the country’s dictator since 1984, had died in December 2008, and was soon replaced by a military junta. The junta held on to power from 24 December 2008 to 21 December 2010, going through two Presidents in the process. It was during this time that Barton’s team struck its deals for farmland.

On 16 September 2010, with Brigadier-General Sékouba Konaté in power, Barton, by way of a newly created company called Farm Lands of Guinea (now Farm Lands of Africa – FLA), signed two deals with Guinea’s Ministry of Agriculture. These deals gave Land & Resources, a subsidiary of FLA incorporated in Guinea and 10% owned by the Government of Guinea, a 99-year lease on more than 100,000 ha of agricultural land. Under a subsequent protocol, signed on 25 October 2010, while Konaté was still in power, Barton’s company agreed to survey and map roughly 1.5 million ha to “prepare it for third-party development under 99-year leases.” FLA maintains that, in return, the Ministry of Agriculture gave it exclusive marketing rights over the lands “with a commission of 15% being payable on closed sales.” When combined, the three deals give FLA control of 1,608,215 ha, or 11% of Guinea’s agricultural land. Late in 2011, FLA reported that its representatives had been prospecting for land in Sierra Leone and The Gambia, and that it had identified 10,000 ha in Mali’s Office du Niger with that country’s Minister of Agriculture.

Friends of Barton:

Craven House Capital: London-based financial firm, formerly called AIM Investments, bought US$1 million-worth of FLA common shares in November 2011.

British Virgin Islands: Provides FLA with a tax and financial haven for its operations.

Going further:

- Coalition Coalition pour la Protection du Patrimoine Génétique Africain (COPAGEN) (contact: francis.ngang@inadesfo.net)

*

“There is no land grab and there will be no land grab. Indian companies should not be constrained by this loose talk.”

“There is no land grab and there will be no land grab. Indian companies should not be constrained by this loose talk.”

The late Prime Minister of Ethiopia

Meles Zenawi and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) have ruled Ethiopia since they came to power in the first elections held after Ethiopia’s civil war in 1995. Zenawi’s power base was in the North and, throughout his rule, there have been tensions with the different peoples of the southern regions of the country, including Oromia, Gambela and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Region. To maintain their power in these provinces, Zenawi and his ministers exercised close control over local authorities, appointing, removing, transferring or even jailing personnel. Zenawi also suppressed dissent by censoring the media, imprisoning journalists, banning opposition parties and community organisations, manipulating elections and deploying the army and police to harass critics of his policies. From March to December 2011, Zenawi had more than 100 opposition politicians and 8 journalists arrested under a catch-all anti-terror law that threatens up to 20-year jail terms for those who merely publish a statement that prosecutors believe could indirectly encourage terrorism. Ethiopia has exiled more journalists than any other country in the world. According to Amnesty International: “Individuals and publications who hold different opinions, represent different political parties or attempt to provide independent commentary on political developments, are no longer tolerated in Ethiopia.”

It is in this context that Zenawi transferred huge areas of land in the southern half of the country to foreign and domestic investors for large-scale agricultural projects. His government identified 4 million ha for this programme, 1 million more for biofuels, and another 5 million for sugar-cane plantations. By the end of 2011, 800,000 ha had been leased to foreign investors. And to prepare the terrain, Zenawi built dams, forcibly displaced communities, and used the army to quell opposition violently.

Zenawi’s ruthless actions did not dampen his international support. Apart from the aid money that continues to flow in from the US, Britain and other northern donors (around US$3 billion per year), Zenawi forged ever deeper relations with India, Saudi Arabia and China, who are eager to support their companies in getting their hands on Ethiopia’s farmland and other resources. Zenawi died of natural causes on 20 August 2012, and the EPRDF has shown no sign of deviating from Zenawi’s land-grab legacy.

Friends of Zenawi:

World Bank – Coordinates international donor assistance that is being used by the Ethiopian Government for a villagisation programme that displaces people to make way for large-scale agricultural projects.

Going further:

- Anuak Justice Council

- Anywaa Survival Organisation, a UK-based group supporting the Anywaa peoples of Gambela, Ethiopia.

- Human Rights Watch report, “‘Waiting Here for Death’: Forced Displacement and ‘Villagization’ in Ethiopia’s Gambella Region”

- Anyuak Media

- Survival International has a letter writing campaign to support the Omo Valley tribes affected by large-scale agriculture projects

*

“Real assets are a real refuge for investors … and gold and farmland are the best assets to be exposed to today and we are doing that in the best way we can.”

“Real assets are a real refuge for investors … and gold and farmland are the best assets to be exposed to today and we are doing that in the best way we can.”

Chairman of Cresud

“We used to have farms, and cows and fruit trees,” says Sofía Gatica, a resident of the community of Ituzaingó, Argentina. “But they destroyed all that and planted genetically modified (GM) soybeans. Now, when they spray the soy, they also spray us.”

Sofia Gatica’s daughter died at just three days old from kidney failure, caused by exposure to the agrotoxins sprayed on the soybean plantations that surround her community. The cancer rate in Ituzaingó is 40 times the national average. It is just one of the communities that has been devastated by Argentina’s massive boom in soybean production, which followed the introduction of Monsanto’s soybeans, genetically modified for resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. Each year, over 50 million gallons of agrotoxins are aerially sprayed on soybeans in Argentina.

The pain for some has been a bonanza for others. One of the big winners from the soybean boom has been the Argentine businessman Eduardo Elsztain, the country’s largest farmland owner and one of its top producers of GM soybeans.

In the 1990s Elsztain was bankrolled by George Soros to purchase undervalued real estate in Argentina through his family company IRSA. They quickly amassed millions, and decided to use some of the profits to take over Cresud, a company with about 20,000 ha of farmland. With another major cash injection from Soros and a public offering on the Buenos Aires stock exchange, Cresud expanded its landholdings dramatically. By the end of 1998 it owned 26 farms covering 475,098 ha. When Soros sold his interest in Cresud and IRSA in 1999, Elsztain found other billionaire friends to replace him, such as Wall Street hedge-fund operator Michael Steinhardt and Canadian tycoon Edgar Bronfman.

Today Cresud’s farmland holdings in Argentina total 628,000 ha, on which it produces mainly GM soybeans and cattle. The company also runs a feedlot operation in Patagonia through a joint venture with US-based Tyson, the world’s largest meat company. Elsztain is now aggressively exporting Argentina’s soybean boom to neighbouring countries. Over the past few years, Cresud’s subsidiaries have taken over 17,000 ha in Bolivia, 142,000 ha in Paraguay, and 175,000 ha in Brazil, mainly for the production of soy. Cresud’s current farmland holdings add up to 962,000 ha.

Friends of Elsztain:

Cargill: The US multinational is one of the largest buyers of soybeans from Argentina.

Heilongjiang Beidahuang Nongken Group: In June 2011, China’s largest farming company set up a joint venture with Cresud to buy land in Argentina and farm soybeans for export to China.

Going further:

- Visit the farmlandgrab.org pages on Cresud

- Sofía Gatica formed the Mothers of Ituzaingó with 16 others. In 2012 she received the Goldman Environmental Prize

*

“It’s like being a kid in a candy store. The opportunities are so immense, and the risks are far lower than people believe.”

“It’s like being a kid in a candy store. The opportunities are so immense, and the risks are far lower than people believe.”

CEO, Emergent Asset Management

Susan Payne is a Canadian who cut her teeth at JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs before embarking on a quest to take over large swaths of fertile African farmland with her British husband David Murrin. Payne and Murrin’s UK company, Emergent Asset Management, launched their African Agricultural Land Fund in 2007, and has since acquired at least 30,000 ha in South Africa, Zambia, Mozambique, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. They claim that it is the largest agricultural fund in Africa.

Payne speaks regularly about the pioneering work she’s doing investing in African farmland. Others might balk at the risks involved in taking over fertile land in African countries where hunger and land conflicts are abundant – and then bringing in white South Africans to run the farms. But Payne and those backing her, such as the Toronto Dominion Bank of Canada, expect a big pay-off. She says that investors in Emergent will get annual returns of around 25%.

In October 2011, the husband-and-wife team announced that they were separating and dividing up Emergent. While Murrin took over Emergent Asset Management, Payne took over Emvest, the joint venture with South Africa’s RusselStone Group, which runs Emergent’s African Agriland Fund and its farming operations.

Friends of Payne:

Toronto Dominion Bank of Canada – Emergent’s largest outside investor

Vanderbilt University – the US university’s endowment fund is invested in Emrgent

Going further:

- Oakland Institute‘s resources and reports on Emergent

- Vanderbilt Campaign for Fair Food

*

“This (700,000 ha rice project in West Africa) is among targets set by the Organisation of the Islamic Conference and the Islamic Chamber of Commerce and Industry to confront the food shortage crisis, increase agricultural output and improve rice productivity,” – Foras

“This (700,000 ha rice project in West Africa) is among targets set by the Organisation of the Islamic Conference and the Islamic Chamber of Commerce and Industry to confront the food shortage crisis, increase agricultural output and improve rice productivity,” – Foras

Dr. Hatim Mukhtar (Saudi Arabia)

CEO, Foras International Investment Company

Hatim Mukhtar could one day be presiding over the world’s largest rice farm. His company, Foras International, is in the midst of implementing a plan to produce 7 million tonnes of rice on 700,000 ha of irrigated land in Africa. Foras started with a 2,000-ha pilot rice farm in Mauritania in 2008, then took a lease on 5,000 ha in Mali’s Office du Niger, and signed an interim agreement for 5,000 ha in Senegal, in the Senegal river valley. The pilot studies in Mali are now complete, and Foras is seeking to scale up its operations to 50,000–100,000 ha. In all three of these countries there have already been tense conflicts over large-scale land grabs.

Foras is still far from its target of 700,000 ha, but Mukhtar has recently signed a flurry of deals that puts the company quite high in the ranks of global farm landlords. Since January 2010, Foras has taken 126,000 ha in Sudan’s Sennar State, along the Blue Nile, signed a memorandum of understanding with the government of Katsina State, Nigeria, for a US$100-million agricultural project that will begin with a pilot farm on 1,000 ha, and started negotiations with the government of the Russian Republic of Tatarstan for 10,000 ha. It is also moving ahead with a US$22 million project to build a massive, vertically integrated poultry farm near Dakar, Senegal, that will produce 4.8 million birds per year. Two companies that Mukhtar met at a business forum in Sarajevo have been brought in to develop its African poultry and cattle projects.

Behind Mukhtar stand some of the most powerful families and institutions of the Gulf States. Foras is a private company, but it operates as the investment arm of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), an intergovernmental organisation with 57 member states that calls itself “the collective voice of the Muslim world”. Its main shareholders and founders are the Islamic Development Bank and several conglomerates from the Gulf region, including Sheikh Saleh Kamel and his Dallah Al Barakah Group, the Saudi Bin Laden Group, the National Investment Company of Kuwait and Nasser Kharafi, the world’s 48th-richest person and owner of the Americana Group.

Friends of Foras:

Islamic Development Bank (IDB) – main shareholder in FORAS

Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) – FORAS is part of the OIC

Going further:

- GRAIN: “Saudi investors poised to take control of rice production in Senegal and Mali?“

- Alliance paysanne « Stop aux accaparement des terres »

*

“Forty-five per cent of the world’s underutilised land and water resources are on this continent. So if we don’t grab the opportunities, someone else is bound to do it.”

“Forty-five per cent of the world’s underutilised land and water resources are on this continent. So if we don’t grab the opportunities, someone else is bound to do it.”

Vice-President AgriSA

Theo de Jager, the vice-president of South Africa’s largest commercial farmers’ union, AgriSA, is also the chairman of its land affairs committee. So he’s been deeply involved in his country’s highly charged land reform, and has even lost a farm of his own in the process. But recently, De Jager has been doing some different work for his organisation: travelling around Africa looking for land that he and other South African farmers can acquire, on a large scale.

De Jager’s first success was in Congo-Brazzaville. The government promised him and his fellow farmers as much land as they might want throughout the country, along with freedom from import duties, taxes and restrictions on the repatriation of profits. De Jager and about 15 other South Africans set up a company called Congo Agriculture, and negotiated a contract with the government for 80,000 ha. The first 48,000 ha were divided into 30 farms for the participating South African farmers. De Jager says that he’s already picked out plots for himself, and intends to produce oil palm, timber and cattle.

But Congo could well be just a first step. As of early 2010, AgriSA has been engaged in negotiations for land deals with the governments of 22 African countries, including Egypt, Morocco, Mozambique, Sudan, Zambia, and even Libya.

De Jager and most of the South African farmers involved in these deals do not intend to live on the land they acquire. They will hire managers and oversee their businesses from afar. It is not so much their knowledge of farming that distinguishes them from the small farmers in the countries where they are acquiring lands, but their access to capital and integration in corporate food chains. De Jager himself moonlights as a real-estate agent; he started farming only in 1997. Before that he was an agent in the National Intelligence Service, serving as “chief information co-ordinator” in the office of the State President during the apartheid-era rule of P.W. Botha.

Friends of De Jager:

Government of South Africa: Supports AgriSA through the negotiation of bilateral investment treaties with the governments of countries where AgiSA is acquiring land.

Government of China: In 2010 AgriSa and China began discussions for a partnership under which AgriSA would help Chinese companies to identify farmland in Africa.

Standard Bank: Along with ABSA Bank and Standard Chartered, is said to be considering funding AgriSA’s foreign farmland projects.

Going further:

- Ligue Panafricaine du Congo – UMOJA (LPC-U)

- Landless Peoples Movement (South Africa)

- Ruth Hall’s paper “The next Great Trek? South African commercial farmers move north”

*

“It’s like the California gold rush. The initial investors are not the most savory characters in the world.” – World Bank’s former Agribusiness Team Leader John Lamb speaking in 2010 about the global land grab.

“It’s like the California gold rush. The initial investors are not the most savory characters in the world.” – World Bank’s former Agribusiness Team Leader John Lamb speaking in 2010 about the global land grab.

The food price crisis of 2007–8 was a public relations disaster for the World Bank. Just months before prices hit their peak, the Bank was still telling governments that food self-sufficiency was a foolish goal. But then the governments of some major food-exporting countries, worried about the needs of their people, began to close their borders. Food prices spiked and riots flared, from Yaoundé to Mexico City, in countries that had followed the Bank’s advice about the efficiency of global markets and the perils of supporting local agriculture. With countries like Malaysia bartering for food, and the number of hungry people and the profits of the grain trade’s giants at all time highs, who could trust the Bank any longer?

Nevertheless, the Bank stuck to its old tune: more export agriculture, more foreign investment. It soon got its wish, in spades.

At the height of the food crisis, a global farmland grab erupted. All the foreign investment that the Bank had for decades promised would be the nemesis of poverty and food insecurity was now flooding into countries all over the planet. But the glaring predicament for the Bank was that the money was chasing farmland occupied by peasants and pastoralists, to produce food crops for export from countries already coping with severe food insecurity. It was hard to spin this as a solution to the food crisis, espcially when the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation’s Director General, Jacques Diouf, had already warned of “neo-colonialism”, and even The Economist was calling it a “land grab”.

But the Bank decided to give it a try anyway. Its answer: a set of “principles for responsible agroinvestment”, and a global report and “knowledge centre” that it hoped would cast the Bank as the objective authority on the issue.

Few were fooled. The Bank’s principles were immediately denounced by social movements, farmers’ organisations and NGOs as a distraction from real action that could stop the land grabs. Its eagerly awaited report was a flop, with hardly any new data to add to what was already known, and with a wishy-washy embrace of the “win–win” potential of “large-scale land acquisitions” in the face of the damning evidence detailed in the Bank’s own report.

Plus, as many groups pointed out, the Bank itself is a land grabber. Through both its Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and its International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Bank has directly invested in companies gobbling up farmland in the South. Among the IFC’s dealings are a US$75-million investment in the Altima One World Agricultural Fund, which has been buying up vast areas of farmland in Latin America, Africa and Eastern Europe and converting it to soybean monoculture, and a US$40-million “risk participation” in financing to the Export Trading Group, which has acquired over 300,000 ha in Africa. MIGA has provided political risk insurance to several companies grabbing farmland in Africa, including the UK’s Chayton Capital, acquiring land in southern Africa, and Unifruit, acquiring land in Ethiopia.

The Bank doesn’t seem to understand why it has been the focus of so much of the opposition to land grabs. It is just “helping smallholders catch the wave of rising interest in farmland,” says the Bank’s land policy specialist Klaus Deininger

Friends of the World Bank:

Governments: the World Bank is run by its shareholders, which are governments. The countries with most voting power are the US (15.85%), Japan (6.84%), China (4.42%), Germany (4.00%), the United Kingdom (3.75%), France (3.75%), India (2.91%), Russia (2.77%), Saudi Arabia (2.77%) and Italy (2.64%).

Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR): The World Bank provides the CGIAR with US$50 million a year in completely unrestricted funds. Some of the CGIAR research centres have developed connections with companies pursuing large-scale farmland grabs.

Going further:

- World Bank section at farmlandgrab.org

- Friends of the Earth International’s campaign to stop land grabbing has a focus on land grabs in Uganda in which the World Bank has been involved.

*

“Improve the agriculture sector in Mindanao, make the farmers there become productive and nobody will take up arms anymore.”

“Improve the agriculture sector in Mindanao, make the farmers there become productive and nobody will take up arms anymore.”

CEO of Agrinurture Inc

In March 2012, China’s ambassador to the Philippines was in central Luzon cutting a ribbon at a new hybrid rice demonstration farm. This was not a simple case of international cooperation. The farm is owned by Beidahuang, one of China’s largest agribusiness companies and perhaps its most aggressive seeker of global farmland, and its local partner AgriNurture. For now, the companies’ farms in the Philippines, covering 2,000 ha, will produce Chinese hybrid rice seeds and supply them to Filipino farmers under contract production arrangements. But eventually the two companies plan to produce the hybrid rice on their own farms. The say that they could have 10,000 ha under hybrid rice production by the end of 2012.

This is just one of the joint ventures that AgriNurture has set up over the past few years with foreign companies for the production of food crops in the Philippines. The company also has a multi-million-dollar banana plantation venture in the works in Mindanao with the People’s Government of Tianyang, Guangxi, China, as well as a farming venture with the Far Eastern Agricultural Investment Company, a consortium of Saudi companies, that plans to acquire 50,000 ha in Mindanao for the production of fruits and cereals.

AgriNuture (ANI) is owned by Tony Tiu, a young Filipino-Chinese entrepreneur and real-estate developer. Since he established the company in 2008, Tiu has quickly built it into one of the country’s leading food exporters, with a focus on fresh fruit. Exports account for about half of the company’s revenues, and about half of those exports go to China. While most of the company’s supply currently comes from contract prodution, Tiu wants to develop his own farms and make these his primary source of supply. Plans are under way to acquire 5,000 ha in different parts of the country for fruit and vegetable farms.

Tiu built up his company through listings on the stock exchanges of both Australia and the Philippines, and through partnerships with the Landbank of the Philippines and the Department of Agriculture, which support his contract production schemes. With more and more land under its control, ANI has itself become a target of overseas farmland investors. In 2011, Cargill’s hedge fund, BlackRiver, which is investing hundreds of millions of dollars in the acquisition of farms in Latin America and Asia, bought a 28% stake in AgriNurture.

Friends of Tiu:

China-Export Credit Guarantee Corp.: it is providing ANI with financial backing for its banana plantations in Mindanao.

Al Rajhi Group: Saudi conglomerate that leads the Far Eastern Agricultural Investment Company, a US$27-million investment vehicle for the acquisition of farmland in Asia, mainly for rice production. It has an MoU with AgriNurture to develop the production of pineapple, banana, rice and maize on 50,000 ha in the Philippines.

Going further:

*

“Our overseas agricultural projects are mainly located in Africa and Southeast Asia where the local agriculture is relatively backward.” – from the ZTE Energy website

“Our overseas agricultural projects are mainly located in Africa and Southeast Asia where the local agriculture is relatively backward.” – from the ZTE Energy website

Chairman and Founder, Zhongxing Telecommunication Equipment (ZTE)

ZTE Corporation is China’s largest telecommunications company, with operations in more than 140 countries. It was formed in 1985 by a group of state-owned companies affiliated to China’s Ministry of Aerospace Industry. While it has been listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange since 2004, ZTE is still closely connected to the Chinese government. Its largest shareholder is a holding company jointly owned by a state-owned electronics research institute in Xi’an and a state-owned company with links to the military. But in 2007, ZTE started to turn its attention to agriculture. It set up a new company, ZTE Energy, to invest in biofuels and food production in China, and to develop overseas farm operations as part of “the strategic plan on agriculture going globally laid down by the central government”.

Hou Weigui and his company are slowly moving ahead with plans for acquiring farmland overseas. In 2008, ZTE purchased 258 ha in Menkao, near Kinshasa, in DR Congo, to study the potential for agriculture five degrees north and south of the equator. ZTE was so happy with the results that it bought another 600-ha farm in DR Congo in 2010. The company also moved into Sudan, where it now runs several cereal farms, and Laos, where it has a 100,000-ha concession in Chapassak Province to grow cassava with its local partner Dynasty Laos.

ZTE has high hopes for palm oil. Although it has put its 100,000-ha oil palm plantation project in DR Congo on hold “because the investment conditions and logistic conditions are not mature,” it is going ahead with a programme in Indonesia and Malaysia, where the company plans to have 1 million ha under production by 2019. At present, PT ZTE Agribusiness Indonesia and its local partner PT Sinar Citra have 10,000 ha in Kalimantan, and are negotiating for another 25,000 ha.

Friends of Hou Weigui:

World Food Programme: ZTE Energy is a “qualified supplier “ of the World Food Programme.

Going Further:

- Laos Land Issue Working Group

- Peasant Confederation of Congo, by way of La Via Campesina