In the land of humongous farms, the critical importance of small farms for food security is a counterintuitive message. But if we look at what most of the largest farms are growing in the U.S. Midwest, or Argentina and Brazil, it is corn and soybeans to feed livestock and biofuel production. Neither contribute much to supplying food—and especially good nutrition—to the billions who cannot afford meat. Meat is a welcome part of many diets, but besides being expensive, is also an inefficient means to produce protein.

Mark Bittman, in a recent article, cites the Etc. Group, which notes that small peasant farms feed about 70 percent of of the global population.

Producing enough food is a necessary, but not nearly sufficient, condition for alleviating hunger. Even though we produce enough food now, 1 billion go hungry. India has more malnourished people than any other country, yet exports food.

Well of course, you may say, there are so many more small farms, it is not surprising that they feed more people than large farms do.

But small farms also tend to produce more per acre than large farms. There has long been debate about this among economists and development scholars. It has perplexed many of them—so much so they have given it a name, “the inverse relationship,” meaning that if graphed, productivity per unit of land goes down rather than up with increasing size. Skeptics have turned the data inside out trying to see if it really holds up.

But a recent paper that carefully looks at the issue using new methods has, once again, confirmed that the higher productivity of small farms does not seem to be an artifact of measurement bias, as has sometimes been suggested.

Recognizing the productivity of small farms has huge policy implications. As the authors note, the productivity of small farms suggests that policies should especially target support to them—the opposite of what we do in the U.S., with our subsidies of a few commodity crops like corn and soybeans that favor the largest farms (small farms should be supported anyway for a number of reasons, but higher productivity can be added to the list). Favoring small farms is also the opposite of what the corporate end of the food system does.

Of course, where small farms have been marginalized on very poor land, and have few if any resources, productivity can be very low. But give them decent land and half a chance and they outproduce large farms under similar circumstances.

Instead of huge land grabs by countries and companies that kick small farmers off their land, we need to get more good land into the hands of more small farms and make sure they have the resources and social support they need.

World Food Prize Comes off the Rails

This situation is yet another reason why the World Food Prize this year is going to the wrong people—developers of genetic engineering that has yet to make a meaningful positive difference, despite providing some small yield increases.

To understand why this year’s prize goes to Monsanto and Syngenta, we may need to look no further than the large money trail that leads from their doors to the WFP organization. Is it a coincidence that a Monsanto scientist is one of those honored with the prize, given the substantial financial support provided by that company (and others)?

Whatever one thinks about the potential of GE to improve food security or availability in the future, it has not done much so far when compared to either the need or the success of other farming methods and technologies.

For example, engineered Bt corn in South Africa, which is a food staple rather than livestock feed, has been reported to provide yield increases of about 17 to 32 percent in one study. That’s good as far as it goes. But it does not go very far. Given the extremely low yields that Bt is building on, these improvements are not very impressive. And they do not improve the general resilience of the crop to withstand the many other problems that can occur from one year to the next, such as other insect pests and disease, drought, floods, and so on.

Only systems approaches, based on agroecology, address the overall resilience of the farm.

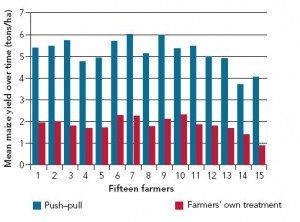

Compare the results for Bt maize in South Africa to the push-pull method, based on sophisticated agroecology principles, designed to grow several crops that complement each other. This method often more than doubles yields (see figure) by controlling the same insect pest as Bt, as well as the worst weed of grains in Africa (striga). It also enriches soil and provides high quality livestock fodder. Women grow one of the complementary crops, desmodium, and make income from selling the seed. And all of this comes without the high costs of transgenic seeds and pesticides.

Adoption has been growing steadily, up about 7 fold since 2006, to about 70,000 farmers last year.

Ironically, one of the main developers of push-pull, Dr. Zeyaur Khan, has been considered for the World Food Prize, but was not deemed worthy.

Smarter Methods

Small farms traditionally have grown multiple crops adapted to local conditions (so-called landraces) as intercrops and in rotations (alternating crops by season).

Alternating crops has consistently been shown to improve the yield of each crop compared to growing them in monoculture or short rotations, such as growing corn, soybeans, or alternating corn and soybeans on over 150 million acres in the US. This has been demonstrated over and over again in developing and developed countries alike.

This is so well known that it is also given a name—the rotation effect. One recent review shows that crops in rotation typically produce 10 or 30 percent more than when the same crops are grown in monoculture or short rotations.

Monsanto’s products have done nothing to reverse the trends toward more corn and soy and more monoculture. So in a sense, they contribute to lower yields than could be attained if we used ecological principles to grow our crops. Another reason why this year’s WFP is a travesty.

The Real Food Prize

Although the WFP has relinquished its claim to relevance, the Food Sovereignty Prize has got it right, honoring the peasant farmers that are the real backbone of global food production. Groups like previous winner La Via Campesina, or this year’s winners, including the Tamil Nadu Women’s Collective, deserve such recognition and support.

They are also the stewards of the critical genetic diversity found in the well-adapted crop varieties they developed and grow, and that we will all depend on to provide traits to improve crops everywhere.

For more on the World Food Prize, see my colleague Karen Stillerman’s blog post, Monsanto Scientist Pockets “World Food Prize”…But For What, Exactly?

About the author: Doug Gurian-Sherman is a widely-cited expert on biotechnology and sustainable agriculture. He holds a Ph.D. in plant pathology. See Doug’s full bio.

Support from UCS members make work like this possible. Will you join us? Help UCS advance independent science for a healthy environment and a safer world.