Tuesday 17 May 2016

Chairman of UN’s joint meeting on pesticide residues co-runs scientific institute which received donation from Monsanto, which uses glyphosate.

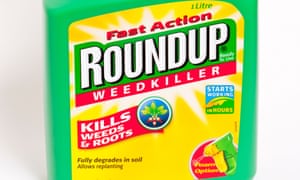

Glyphosate is a core ingredient in Roundup weedkiller, made by Monsanto. Photograph: Studioshots/Alamy

Professor Alan Boobis, who chaired the UN’s joint FAO/WHO meeting on glyphosate, also works as the vice-president of the International Life Science Institute (ILSI) Europe. The co-chair of the sessions was Professor Angelo Moretto, a board member of ILSI’s Health and Environmental Services Institute, and of its Risk21 steering group too, which Boobis also co-chairs.

In 2012, the ILSI group took a $500,000 donation from Monsanto and a $528,500 donation from the industry group Croplife International, which represents Monsanto, Dow, Syngenta and others, according to documents obtained by the US right to know campaign. Boobis was not able to comment on the issue, and ILSI’s office in Washington did not immediately respond to a request for more information.

But the news sparked furious condemnation from green MEPs and NGOs, intensified by the report’s release two days before an EU relicensing vote on glyphosate, which will be worth billions of dollars to industry.

Vito Buonsante, a lawyer for the ClientEarth group, said: “There is a clear conflict of interest here if the review of the safety of glyphosate is carried out by scientists that directly get money from industry. This study cannot in any way be reliably considered when deciding whether to approve glyphosate.”

The Green MEP Bart Staes said: “The timing of the release of this report by the FAO/WHO could be described as cynical, if it weren’t such a blatantly political and ham-fisted attempt to influence the EU decision later this week on the approval of glyphosate.”

The WHO says that from its side, the timing of the report’s release so close to the EU decision was coincidental, and was decided several months ago.

The debate over glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide in human history, has become a lightning rod in Brussels, because of its widespread use with crops genetically engineered to resist it. Its use has also been led to reports of associated damage to human health, nearby flora, insects and animals.

The debate over the scientific bona fides of the ILSI also has a fractious back story. In 2012, the European parliament suspended funding to the European food safety authority (Efsa) for six months over a string of conflicts of interest allegations involving ILSI members on the board of Efsa and on its committees.

The dispute saw the resignation of the chair of the Efsa management board, as well as Moretto standing down as a member of the Efsa pesticides panel, for failing to declare links with the industry and ILSI. An advisory position held by Boobis at Efsa was discontinued in 2012. At that time, ILSI described itself as a “key partner for European industry”, but it now says that it is a non-profit guided by scientific and environmental concerns and that it does not lobby or make policy recommendations.

This description of the group was endorsed Dr Philippe Verger, a WHO official and secretary of the UN panel on glyphosate. He said that ILSI could best be called a “meeting place” for scientific discussions.

Verger told the Guardian: “ILSI is not an independent body. That is very clear. Private companies are supporting it and its structure. But the objective of ILSI and of the companies is to create a space for discussion and interaction between the private and public sectors. ILSI’s focus is not to discuss topics of economic interest for individual companies. It is more of a forum.”

The UN panel’s conflict of interest explainer says that it will exclude experts who have “forms of economic relations that may undermine [their] neutrality”.

Greenpeace was not convinced, however. Its EU food policy director, Franziska Achterberg, said: “Even Efsa – not exactly a poster child when it comes to impartiality – doesn’t allow scientists tied to ILSI to sit on its expert panels. Any decision affecting millions of people should be based on fully transparent and independent science that isn’t tied to corporate interests.”

In common with an Efsa assessment that also attracted anger from environmentalists, the JMPR’s decision was taken on the basis of confidential industry dossiers not available to the public.

A separate report last year by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – WHO’s cancer agency – which only considered publicly available studies, concluded that glyphosate was probably carcinogenic to humans. But WHO officials maintain there is no contradiction between the two papers, noting that IARC was identifying a potential hazard, whereas the JMPR was quantifying the associated risk.

Verger said: “Every year we evaluate 10-30 compounds, and I can tell you that a lot of them are more dangerous and potent than glyphosate. We are a bit uncomfortable that there is so much interest in this assessment, [just] because this particular pesticide is used for GM crops.”